#1 Good street form defines the character of a city

Streets define neighborhoods and neighborhoods define cities. Streets make up 80% of US cities’ public space, more than parks and plazas combined. They are the primary experience of the city, and the reason people want to be there because they are places to relax, meet, do business, and enjoy life. Good street design recognizes streets as an essential feature of the city, defining its physical and cultural character.

Streets are places where people socialize, relax and enjoy life

Approach streets as places of opportunity

Streets are the ubiquitous public realm nearly everyone touches on a daily basis. They give a city its distinctive feel. As such, they hold all of society’s joys and sorrows. Embrace the opportunities this brings.

Streets function as essential public places, like parks and plazas

Streets make up most of our public space in cities. A healthy street is also a pleasant place for humans to inhabit - which naturally fosters community connection and contribution. Thus, good street form optimizes for place, and by so doing defines the distinctive character of that place.

Streets are places first

Streets must be designed as places first, even when they are also paths for people and goods to get from A to B. Not only do streets connect us to the places we want to go, they are the places where everyday life unfolds. Streets are more than just sidewalks and facades—they are what enables cities to become more human and the entirety of public life to take place. They allow us to connect with the identity of a city and with each other. In especially dense urban areas, streets provide essential space for living - effectively functioning as backyards, garages and even living rooms.

Good streets are designed as one cohesive place

We experience the street as a continuous space, yet they are usually designed through disjointed projects by different entities and actors. The space between buildings should be approached as one holistic experience. This requires coordinating public entities that make and care for the streets around a set of shared values that consider the way the street feels to those who use it. For example, designing building facades as part of the street before considering them part of the building.

Good streets are designed as one

“In a city the street must be supreme. It is the first institution of the city. The street is a room by agreement, a community room, the walls of which belong to the donors, dedicated to the city for common use. Its ceiling is the sky.”

We might be driving one minute, but next we will walk down the street and then sit for a coffee. A kid biking in circles around the neighborhood is not commuting, but playing in a place. We might spend 15 minutes reading in a bus stop before getting onto a bus.

#2 Good street form embraces the human scale

Street form should be optimized for the abilities and limitations of people first. This means designing streets that are safe and inviting at eye level, comfortable and delightful to our senses, and that actively invite interaction between people. Good streets help provide people with dignity and ease in their day-to-day life by prioritizing access to opportunity, goods, and services, over speed.

Street space should be equitably distributed for people

Design for people

Good streets are designed for people first, not the mobility technology that moves them. Human beings are diverse. Yet, as a human animal we share many similar abilities and limitations with our species. Our sensory development is closely tied to the landscapes in which we have survived over millions of years. It is only in the last few thousand years that our senses, which developed through a long biological history, have been used in the context of cities. And it is only in the past five decades that we have planned the cities from above rather than from the eye-level perspective of walking humans. [1]

Turning knowledge of the human senses into street form helps us to create comfortable, attractive and liveable places in cities. We know how far we can see and what we are able to perceive at different distances. We know the limited angles that our eyes can see up and down. We know we generally walk at a speed of 5km/hr and see the world from an average ground height of 5'5". We see in front of us, at a slight downward angle, meaning the first floor of buildings are the most important to us. Our senses are important to our sense of safety and pleasure. We need 1,000 stimuli every hour - that’s one every 4 seconds to feel interested in a space. In order for our cities to be designed at the human scale, they must consider the constraints of human speed and perception.

Prioritize protection, then comfort, and finally enjoyment

Quality streets have elements of protection, comfort, and enjoyment. These three themes can be thought of as a hierarchy of needs in a space. Without basic protection from cars, noise, rain, and wind, people will avoid spending time in a space. Protection from these things is mandatory for a place to be used. Second, without elements that make walking, standing, sitting, seeing, and conversing comfortable, a place won’t invite people to spend time there. Finally, a great place distinguishes itself from a good place by including elements that invite people to be active and make use of the positive aspects of microclimate and human scale. Decades of developing this approach through research and practice at Gehl have shown that aesthetic qualities of a space are only one of the important things that influence whether or not a public space is appreciated or used. “Beauty” in a traditional sense is important, but it comes last. Learn more about Gehl’s 12 Urban Quality Criteria here.

Prioritize proximity over speed

Many cities were planned with our daily needs intentionally far away from our home and work. In the past, we optimized our streets for speed so we can get to these places quickly. But, we can also bring our daily needs closer to us by creating opportunities for work, community, shopping, and entertainment closer to our homes. By optimizing our streets for proximity instead of speed, we achieve the goal of access by being able to carry out our daily needs without the need for speed or unnecessarily lengthy trips.

Prioritize the most vulnerable

Streets that prioritize the most vulnerable are good for everyone. Older people, younger people, and those with mobility challenges move more slowly and are less protected in public space. People who face discrimination in the public realm based on their identity cannot rely on the same protections of the law as others. Good streets are designed intentionally for the comfort and safety of their most vulnerable users. If streets are made for all people, of all genders, of all races, of all abilities and mobilities, from age 8 to 80, all people will be comfortable there.

Design for value beyond money

In Danish the word Herlighedsvaerdi is often translated to Enjoyment in English. However while “enjoyment” carries with it a connotation of “fun”, Herlighedsvaerdi means, more fully, to be delighted and stimulated by the details, meaning, and place-based character of the world around you. It is sometimes translated as the value of a thing when the economic value is extracted. It can be used to describe things like a view of the sea, silence, natural beauty, or animal life – public goods that anyone can share without “using them up”. Another word for it might be “pricelessness.”

Human-scale human-speed urban environments respect our senses

[1] Life between Buildings, Gehl

Design for the human scale with varied housing typologies and mixed use buildings that activate streets and bring amenities to neighborhoods

“When you walk through a city at five kilometers per hour, it’s a very sensual and interesting experience. So we design cities for people at the scale of 5 km/h. Suburbs are made so that cars are happy going 60 km/h. That’s a completely different scale from walking. We are building for ourselves problems of obesity, social isolation and financial hardship with the patterns of our car suburbs.”

#3 Good street form forgives

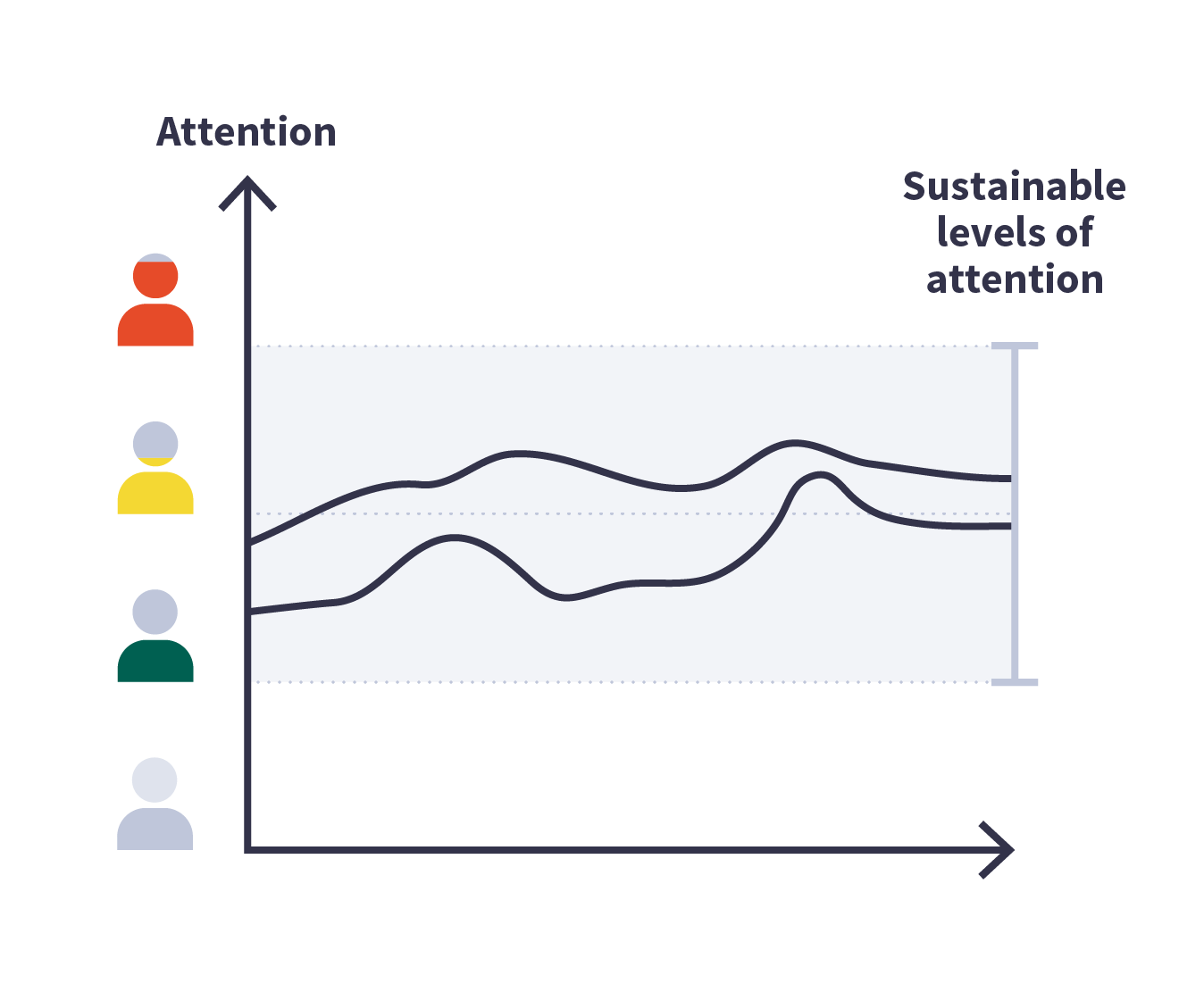

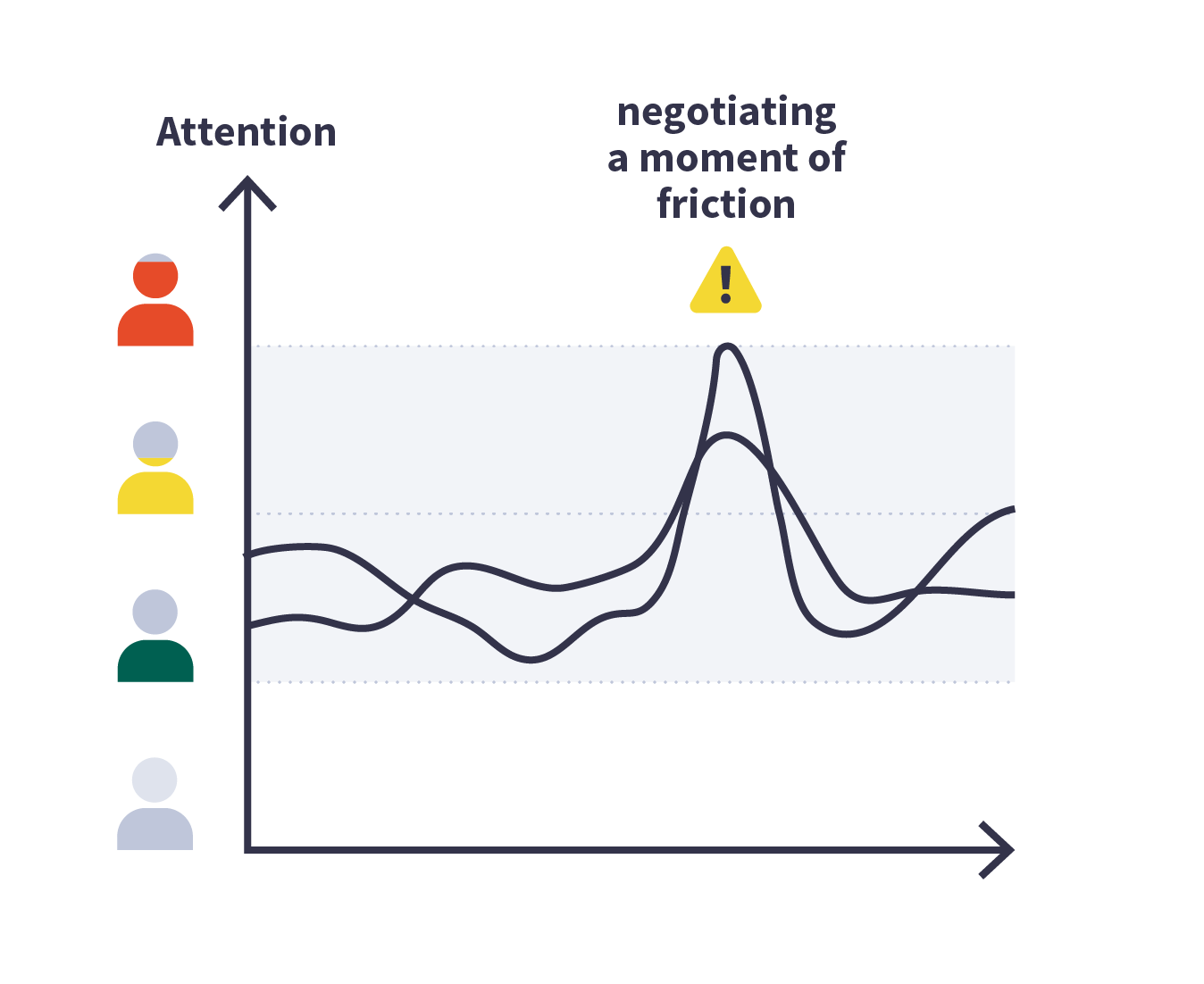

Good street form accommodates a range of mistakes and inattention. Good streets do not demand an inhuman level of attention in order to stay alive, and the consequences for breaking a rule are low. One mistake should not mean disaster. On a good street, because your attention is not exhausted by rules, you have the bandwidth to enjoy the experience of being on the street.

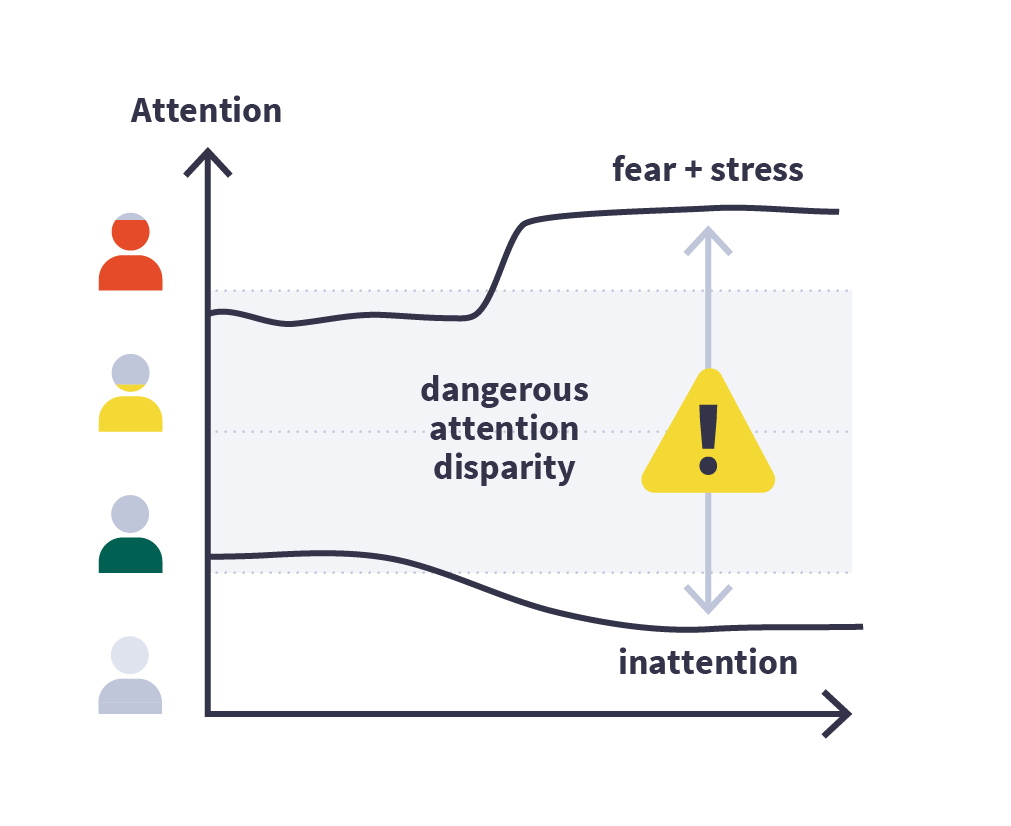

Today, the unwritten rule of the street is ‘Pay Attention! Don’t Die.’ Streets designed for cars require constant attention from humans. The price of not paying attention in the street is high, leaving people in the street stressed and afraid. In response to fear, we create rules restricting choice, encouraging speed, and ultimately raising the stakes for error. This creates a vicious cycle of increased speed and more rules.

Human rules based on human attention

Good streets foster a type of attention that allows a sense of place and human connection to happen. There are two basic types of attention: Vigilance and Fascination.

Vigilance is voluntary, focused attention. We pay vigilant attention to tasks like looking for a book on a bookshelf, or driving a car. Fascination is the involuntary attention we give to our environment. Environments of constant vigilance are untenably exhausting for people, while fascination is thought to restore capacity for other kinds of attention. Streets with fast moving people in cars that mix with people moving slowly require a high level of vigilance to ensure that no one is hurt. Most streets have created rules that optimize for predictability of people driving to create an illusion of safety.

Paradoxically, many of these rules create such dull environments they allow drivers to be inattentive on the street, shifting the burden of vigilant attention to more vulnerable people on the street. The inability to maintain constant vigilance is a normal aspect of being human. Environments that demand constant vigilance from vulnerable people on the street is a systemic flaw of vehicle and street design. Good streets support rules that allow you to selectively pay and receive attention without fear for your safety and livelihood. Design streets to allow people to feel fascinated by their environment and restore our ability to pay vigilant attention when we need to, while enjoying being human in the street.

Good streets foster a type of attention that allows a sense of place and human connection to happen

#4 Good street form supports a range of interactions

Good street form creates the conditions for a range of interactions - from passive interaction, to civility, compassion, even anger. Good streets give people genuine reasons to interact - whether that means hearing someone else talking, having a reason to sit down next to a stranger, visit a shop, or recognize a familiar face from a daily commute. On a good street, these interactions may grow into a feeling of civility, empathy, and even compassion.

Donald Appleyard's study on livable streets compared 3 residential streets with varying vehicular traffic volumes. He found that people who live on streets with light traffic have more friends and acquaintances than those who live on streets with heavy traffic.

Invite public life

Public life is the shared experience of the city created by people when they live their lives outside of their homes, workplaces and cars. It is the everyday life that unfolds in streets, plazas, parks, and spaces between buildings. Public life thrives when all people can enjoy being in public together, and is encouraged by quality public space that fosters social interaction.

Many streets have designed away invitations for public life, leaving people with few reasons to interact. These streets lack the features that would make comfortable and inviting environments and without conditions for interaction end up alienating people from themselves and from others. Before achieving a street that supports empathy or compassion, streets must first be places for interaction. This interaction means streets can’t be built around principles of efficiency. They must be built for public life, interaction, and leave room for chance, a little bit of friction, and human experiences.

Create conditions for civility and compassion

Streets are one of the primary places where we create and reinforce social norms of civility and compassion. Interaction is the starting point for empathy between different people, yet, not all interaction leads to empathy. Sociologist Ryan Enos finds that “It is the presence of a group that is proximate, yet segregated—close but far—that precipitates the politics of division.” When interaction between segregated groups is too brief or too superficial, social mixing results in an exclusionary impulse. To move beyond superficial interactions, create genuine invitations for groups to interact through prolonged contact or interpersonal interaction.

While empathy is a positive social feeling that can broaden a set of beliefs around who belongs in the street to be wider, more tolerant, and more welcoming, we can’t stop at feelings - streets can turn empathy into compassionate actions. Good streets foster a sense of compassionate agency for all people on the street, to encourage action that makes the street a place for everyone.

Celebrate surprise

Good streets are rich in detail and public life, with opportunities to discover new things. The possibility of surprise and a rich experience is offered when streets are articulated, human scale, and full of life. Serendipity offers the possibility of joy and creativity. It’s what makes moving in the street interesting and meaningful.

[2] Knight Foundation/Gallup “Soul of the Community” three-year survey-based study of 26 communities (2010)

[3] Ryan D. Enos and Christopher Celaya, “The Effect of Segregation on Intergroup Relations” Journal of Experimental Political Science (2018)

“Our common spaces have the potential to strengthen community bonds and expose people to difference, and that even indirect passive social interactions can foster a sense of belonging. It’s little surprise then that zip codes in which neighbors live closer together often have higher rates of civic engagement and tolerance for difference.”

#5 Good street form invites participation

Good street form expresses the soul of the community by being created collectively. Whether this means passive participation by walking down the street, active participation by adding a notice to a community bulletin board, or political participation by showing up at a community meeting, streets are a rare space in society that is possible only through the participation of the people that are in it.

Soulful streets are created and shared collectively

Allow for flexibility, change, and friction

Good streets are dynamic. They allow for people to participate in their own way, at different times and in different ways. Streets are for all, which sometimes means that some people want different things out of streets based on their needs. Good streets make room for this friction.

Use experiments, pilots, demonstrations, art projects, performances, or temporary installations to test what people want before a big investment

Improve street design by bringing more people into the process through experimental design that can test ideas quickly. Use feedback from a broad user group to improve a design.

Remove barriers to resident-driven activities

Free or low-cost block party and event permit fees, streamlined application processes with short turnaround times, street-level power outlets, funding for neighborhood groups, and event resources available to the public are all ways to encourage people to be active participants in making their streets.

Honor legacy and community

Our streets carry and honor our history - the people, places and moments that have shaped them. Streets with soul give our lives meaning. Communities’ social offerings, openness, and aesthetics are, in that order, most likely to influence residents’ attachment to their communities. Cities people love also have higher well-being and stronger economic growth. [2]

[2] Knight Foundation/Gallup “Soul of the Community” three-year survey-based study of 26 communities (2010)

Good streets invite you to participate in making them